It’s Tuesday, and today we’re talking about Kofa, an energy tech startup from Ghana. Founded in 2022 by Erik Nygard, last year the company raised $8.1 million in a pre-Series A round consisting of equity, debt, and grants, co-led by E3 Capital and Injaro Investment Advisors. The investor list also includes Mercy Corps Ventures, Wangara Green Ventures, and PASH Global, among others.

The Context

Kofa is building a battery-swapping product that covers multiple use cases. At its core, though, the company is helping businesses and households struggling with power reliability, as well as motorbike owners dealing with fuel prices. All of this is tied to a broader issue of emissions.

So let’s go over each of the three points.

Power Reliability

Unlike many of its neighbours, Ghana doesn’t experience major issues with electricity access, with 89.5% of the population connected to the grid, among the highest rates on the continent. Paradoxically, Ghana’s enterprises experience power outages at a slightly higher rate than other sub-Saharan African countries: 73.8% vs 72.9%.

The reason behind these widespread outages is debt. The country owes $2.5 billion to independent energy producers. About 60% of that debt was paid out just last year; however, outage risks remain.

To cope with outages, 94% of companies resort to power generators, which tells us two things. First, there is willingness to pay. Some of that willingness comes from the fact that businesses lose more money from stopping operations than from spending on backup power. But it also shows that there is access to capital to spend on that power. Second, there is an established secondary power market operating in parallel with the formal one.

Fuel Prices

We’ve talked a bunch about motorbikes in Africa, including last week with Anda. It’s an established fact that motorbikes sit at the core of transportation across the continent, including Ghana. There are ~800,000 motorbikes on Ghana’s roads, and all of them need fuel.

As with electricity, supply reliability isn’t the issue. Where there is an issue is with price. And it’s a two-fold problem.

First, prices are volatile. Between 2020 and 2024, petrol prices surged by roughly 150%, while diesel rose about 200%, with most of the increase attributed to the depreciation of the Ghanaian cedi. Regardless of the reasons, this volatility doesn’t help the drivers.

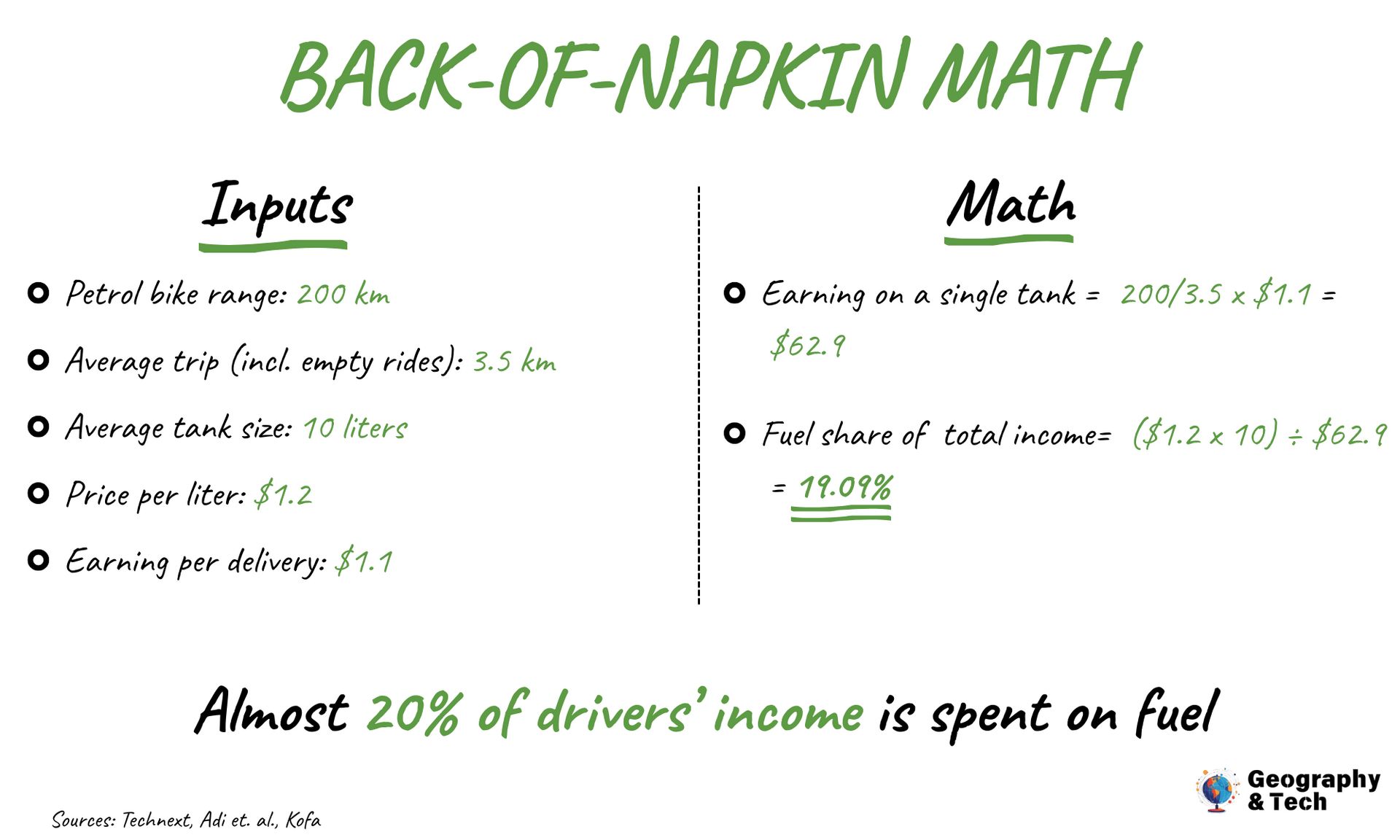

The second, and more pressing issue, is the price level itself. Today, Ghanaians pay around $1.3 per liter. How much of total income goes toward fuel is still debatable. Some sources suggest around 40% (here or here, though not Ghana-specific), while others are closer to 10%. I got to roughly 20%.

But while the exact figure is important, what’s key is that fuel costs are clearly dragging incomes down, especially in absolute terms. When earnings are in the hundreds of dollars at best, and fuel prices are higher than in Australia or Canada, drivers not doubt feel it.

Emissions

I won’t bore you with random factoids about the harm of petrol fuel. We all know that.

But it’s important to look at fuel consumption through an efficiency lens. One study found that motorbikes emit 16 times more hydrocarbons and 3 times more carbon monoxide compared to other types of vehicles moving the same number of people.

You can’t get rid of bikes because they are the most affordable mode of personal transportation in the region. Still, it’s hard to ignore that on a per-person basis, they are the most environmentally harmful option.

The Broader Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa as a whole experiences the same problems, just at a deeper level. There are more outages than in Ghana, electricity sources are dirtier, and overall incomes are lower.

While Kofa was founded in Ghana due to circumstance, it is addressing problems experienced across the sub-region.

The Product

What does building a battery-swapping product entail? In Kofa’s case, the solution consists of three elements:

The battery, equipped with an IoT board that helps manage energy and provides usage data. As the battery degrades, it can be repurposed for less intensive applications. Each battery has a 2.3 kWh capacity, with one bike carrying two batteries, giving a range of roughly 80-100 km.

The network of swapping stations, where motorbike owners, businesses, and households can pick up a charged battery and leave a depleted one. Today, there are ~40 swapping stations around Accra.

The software platform that ties batteries and stations together. The IoT device delivers data such as speed, location, state of charge, temperature, and other indicators to the software layer.

While batteries and swapping stations are the tangible part of the business, Kofa positions itself more as a software company.

Source: TAILG

It’s building a single ecosystem where operators (ride-hail companies, logistics providers) can monitor energy usage and uptime, and where drivers can find swapping stations and check energy availability. The ecosystem is powered by KofAI, which predicts demand, plans optimal battery distribution across stations, and uses historical swap data to improve service reliability.

The platform also helps Kofa adapt to local realities. Because electricity supply can be unreliable, charging must be managed carefully to avoid putting too much strain on the grid.

Now, while the reserve power component exists, the primary use case today is still motorbikes.

To get the business off the ground, Kofa had to build its own bike suited to Accra’s streets. Which they did. The model is called TAILIG Jidi, developed in partnership with TAILIG, a Chinese electric two-wheeler manufacturer. When customers buy the bike, it doesn’t include the battery — they rely on Kofa’s infrastructure to access batteries through the swapping network.

The plan is to deploy 200,000 bikes supported by 5,000 swapping stations by 2030, helping riders adopt more eco-friendly transportation while saving up to 30%.

If that rollout succeeds, the swapping network effectively becomes a distributed battery infrastructure layer across cities. Kofa’s vision is to become a distributed mini-grid that can provide electricity backup for nearby mission-critical services, powered by solar energy and connected into a single network.

The Business Model

I think there are two reasons why Kofa is betting so much on the software layer.

First, it’s difficult to build a moat in battery technology and swapping infrastructure alone. The business is capital-intensive and requires significant R&D. If you aren’t the best-capitalized player, it’s unlikely you’ll build the largest network. And when it comes to battery technology, competing with Chinese companies is particularly hard: they not only have more experience but are also the ones manufacturing the batteries themselves.

Second is utilization. Because fixed costs are high, the company needs as many batteries as possible in use at any given time. Charging batteries is close to free, so the higher the utilization rate, the better the unit economics. This also explains why the company isn’t targeting just one use case. It needs to aggregate as much demand as possible to generate returns on each station quickly.

While hardware is the product and the primary capital investment, software is what will ultimately determine differentiation. If multiple operators deploy similar batteries and stations, the platform that manages utilization, routing, pricing, and reliability across the network the best — wins.

Monetization

Kofa offers customers two ways to pay for batteries: a monthly subscription or a pay-as-you-go model.

Results

The company handles about 14,000 swaps per month, supporting roughly 500 riders. It is scaling in Accra and entering Kenya, with plans to expand across sub-Saharan Africa.

The Bear Case

Two reasons why you can be bearish about the company.

The thing that can give you pause in any swapping business applies here as well: you need a lot of upfront capital to establish distribution. Without that distribution, motorbike owners will be wary of switching to electric vehicles, creating a classic chicken-and-egg problem. You can’t have enough customers to justify investing more capital into the swapping network. But until you have the network, you won’t have the customers.

Kofa also makes the case that in the future multiple manufacturers will support its battery. That means, in a way, Kofa’s success is not determined by Kofa, but by manufacturers. They would not only need to agree to build compatible models but also help distribute and promote them.

And if charging infrastructure develops faster than swapping networks, manufacturers will have little incentive to invest in bikes with swappable batteries.

The Bull Case

Acquiring enough partners and scaling the swapping network would allow Kofa to lock in customers for years. If a customer changes bikes every three years and needs a swap every two days, that’s roughly 550 swaps. That starts to look like SaaS-level customer lifetime.

The mini-grid vision is also compelling. Becoming integrated into energy infrastructure resembles B2C lock-in, but over an even longer time horizon and with higher switching costs.

Finally, if Kofa can get ride-hailing providers and other B2B customers to adopt its bikes, it again creates long-term lock-in. The software layer would, in this case, be responsible for managing costs and helping both drivers and operators improve margins.

So regardless of how you look at it, the bull case is ultimately about lock-in.

The Takeaway

What’s the one lesson investors and founders can take away from Kofa?

As Erik Nygard mentioned in one of his interviews, to be a founder you almost have to be a bit crazy. Someone capable of focusing obsessively on a hard problem and believing in the idea more than anyone else. Building something like Kofa requires that level of conviction. But it also requires discipline: focusing on the core offering and not getting distracted when the initial challenge is already difficult enough.