It’s Tuesday, and today we’re looking at Oben Electric, an Indian electric motorbike company founded by Madhumita Agrawal, Dinkar Agrawal, and Sagar Thakkar. They recently closed an extended Series A round with backing from both new and returning investors, including Helios Holdings, the Sharda family office, and the Kay family.

The Product

Some businesses have a unique product, but a basic business model. Take Sugru, a moldable glue that turns into rubber — but nothing special about how it’s sold.

Others are the other way around.

Oben Electric is definitely more of the latter than the former. It sells electric motorbikes, which on the face of it aren’t that unique — there are plenty of electric two-wheeler (E2W) manufacturers nowadays. What’s interesting is the model, which in turn makes the products unique in many ways, though that uniqueness is largely hidden from the customer.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Let’s focus on the actual product first.

The company offers two models:

Rorr. This was the company’s first product, using an 8 kW IPMSM motor and a fixed 4.4 kWh battery. It has a claimed range of 187 kilometers and a three-second 0–40 km/h time. Charging to 80% on a household 15 A outlet takes roughly two hours. At launch, the bike cost ~$1,800. This was more of a high-end option, positioned against 150 cc petrol motorcycles.

Rorr EZ. In 2024, the company introduced the Rorr EZ to reach a lower price segment. It has a 7.5 kW motor (0–40 km/h in 3.3 s, 95 km/h top speed) but offers three battery options: 2.6 kWh for 110 km, 3.4 kWh for 145 km, and 4.4 kWh for 175 km. Prices range between $1,200 and $1,500.

Judging by local marketplaces, the Rorr is more of a upper-mid market offering, and Rorr EZ slots in the mid-market segment.

With the bike comes a 3 year or 40,000 km battery warranty, 3 year engine warranty — both standard for the industry with Ola standing out on the battery side with the 8 year warranty.

Now, aside from the bike you also can get several add-ons.

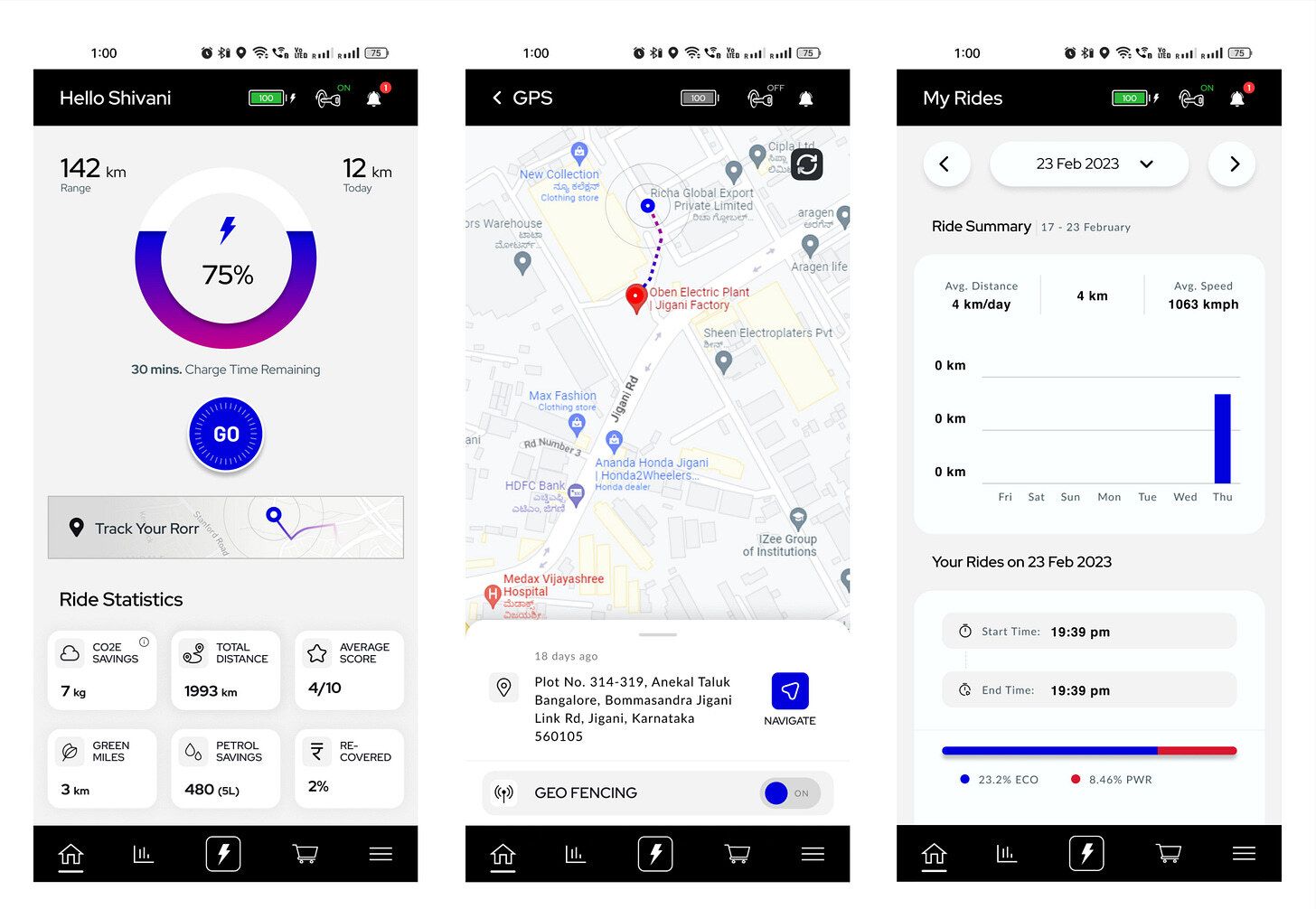

First is Oben Care, a yearly service plan with two options: Premium and Platinum. Both include two free scheduled services and body washes, plus a 10% discount on parts. The Platinum plan adds roadside assistance as well as access to app and data services. The app includes features like estimated charging time, driving efficiency stats, and other telematics.

Next, there’s an extended battery warranty that goes up to 8 years or 80,000 km. Finally, Oben Plug — a small charging station that you can mount on a wall and use to charge the bike.

Before we go to the business model, I have to say I find the supplemental offerings confusing. For instance, the Rorr page mentions Oben Care and it seems to be included in the bike’s price — but maybe it’s not. And it’s hard to figure out how much it costs. Same goes for the app: you can download it, but what data you get for free, you don’t know. So I think there’s a lot of work the company has to do on the product packaging side.

The Business Model

The essential part of the business model — and Oben’s main feature — is vertical integration. It designs, develops, and manufactures critical components in-house, including batteries, motors, vehicle control units (VCUs), and chargers. At its production facility in Bengaluru, Oben has an installed capacity of 100,000 units per year, with plans to significantly expand production by 2027. The company also sells and services its bikes directly.

The goal is to control the supply chain, improve margins, optimize costs, and reduce reliance on external vendors. It should also help with product quality, since key components are purpose-built in-house.

To understand what vertical integration actually enables, let’s look at each major part of the value chain:

Battery manufacturing. Oben isn’t the only company assembling battery packs — most OEMs do that. But it is the only one betting on Lithium Ferrous Phosphate (LFP) batteries in the Indian two-wheeler market. Despite having lower energy density (and thus being heavier), LFP batteries offer better heat resistance, more charging cycles, and greater chemical stability — traits that Oben believes are better suited to India’s tropical climate. The company also plans to co-develop battery cells1, a much more R&D- and capital-intensive part of battery manufacturing.

Motor and power electronics. Oben develops its own motor, controller, VCU, and related components. That unlocks two advantages. First, it improves customer experience — things like throttle response, battery life, thermal stability, and overall performance. Second, it allows for tighter quality control. Every bike coming off the production line goes through a 52-point quality check, with the company reporting a 95% straight pass rate2.

Charging. Oben has developed a home fast charger that plugs into a standard 15-amp socket and can deliver an 80% charge in two hours — faster than most competitors.

Sales. The company sells directly. It currently produces 500–600 bikes per month and distributes them through 20 stores where customers can buy or test ride the product. Another 30 locations are planned this year, with a long-term goal of expanding to 150 stores across more than 50 cities. Oben may eventually use a dealer network to scale distribution (something we also touched on last week). But for now, direct sales allow better unit margins, more competitive pricing, and tighter control over the customer experience.

After-sales service. By integrating its own service operations, Oben gains deeper insight into its product — with multiple benefits. The most important: Oben can resolve problems fast. According to CEO Madhumita Agrawal, this is why most issues are fixed within 48 hours, and why service data show 90% of cases closed within 72 hours. That speed is enabled by both the integrated manufacturing setup and the fact that service teams are focused on just one brand. It also helps build customer trust — if something goes wrong, Oben has a clear path to fix it. And finally, there are strong feedback loops: the more bikes are sold and serviced, the more problems can be identified and addressed. Because service and manufacturing are integrated, Oben can fix the root cause faster.

Compared to other E2W manufacturers in India — and there are many — Oben is one of the most vertically integrated. The only real peer in this regard is Ola, one of the market leaders.

So with all that, here’s the key question:

If you’re a buyer looking purely at specs, does this integration actually help?

The answer, surprisingly, is yes. In the same price range, with top-end specs (speed, range), there are basically five options3 — and two of them are Oben.

What we don’t know yet is how that will impact Oben’s business at scale. Will it drive better margins in the long run? Will it lead to significantly higher product quality — enough for Oben’s reputation and customer base to grow faster than the rest?

The Local Angle

Motorbike popularity

India is the motorcycle capital of the world. Globally, the industry generates around $43 billion in sales — and India accounts for $23 billion of that. Last year, nearly 19 million motorbikes were sold in the country. Today, over half of Indian households own a motorbike, with roughly 260 million vehicles on the road.

Now to the electric part — a market that’s booming. In the last two years, the number of electric two-wheelers (E2W) sold in India has nearly doubled, reaching 1.1 million last year. Ola Electric dominates with almost 40% market share and growth of over 50%. TVS holds second place, selling more than 219,000 bikes last year with 32% growth, while Bajaj comes in third with 192,000 units and 168% growth.

Now, all this is great, but the E2W market is actually structured differently compared to ICE bikes. By my rough estimate, scooters comprise about a third of the overall 2W market. In the electric segment, the picture is different. Of the 1.1 million E2Ws sold last year, 700,000 were scooters. However, and very importantly, that figure does not account for companies selling both scooters and motorcycles. So the actual difference is even larger.

So, while Oben is targeting a mass-market segment, in the EV space that segment is relatively small today.

Key drivers

Now, I don’t think today’s market structure will matter much in the long run — simply because of how long a runway EV producers have. And with all that continued growth, the natural question is: what’s actually driving the market?

Incentives. I would say the biggest growth lever is government support — specifically, subsidies. The main national scheme is FAME, which has gone through several phases. Phase II offers an incentive of ₹10,000 per kWh, capped at 15% of the ex-showroom price. On top of that, many states have their own incentives. For example, Delhi provides ₹5,000 per kWh, capped at ₹30,000. I’ve given numbers in dollars before, but to put it in perspective: taken together, these subsidies reduce the price of an Oben Rorr by roughly 20%. Another big move by the government was to cut the goods and services tax on E2Ws to 5%, compared to 28% for petrol bikes.

Anti-ICE regulation. The government isn’t just supporting EVs — it’s also squeezing ICE vehicles. Delhi is a standout example: local policymakers plan to ban the sale of ICE two-wheelers by 2027, which would instantly make it the world’s largest E2W market.

Charging. Charging infrastructure is improving rapidly. The number of public stations has grown from just 1,800 in 2022 to 16,000 in 2024 — nearly a nine-fold increase in just two years.

B2B. Corporate sustainability goals are pushing demand. This is especially true in the digital economy. One example is Zomato, which already has 37,000 EV delivery partners and recently began renting 300 more e-bikes, aiming for 100% EV deliveries by 2030.

Things are looking great for the E2W space — but every rose has its thorn. Or several, in this case.

Challenges to overcome

We can group the key challenges into three buckets:

Incentives. Yes, incentives again. Earlier I mentioned FAME and its second phase. Well, that phase is over, and a new scheme has been introduced, which is expected to increase E2W costs by around 10%, according to estimates. We’ll see how it plays out, but it could turn away at least some buyers.

Infrastructure. Charging infrastructure has been improving, but not fast enough. Some estimates suggest India will need 160,000 chargers by 2030 to keep up with demand. And unsurprisingly, existing stations aren’t distributed evenly — for example, Andhra Pradesh has just one public charger for every 205 kilometers of road.

That said, I don’t think any of these challenges are insurmountable. The market will likely keep growing. Who comes out on top, though — that’s a whole other question.

The Bear Case

The company’s main bet is that integration will be the thing that wins out — that with scale, per-unit costs will drop, and product quality and efficiency will outpace the competition. That’s a big bet.

In the automotive world, there aren’t many scaled EV players aside from Tesla and a few Chinese giants. And in that space, the market five or ten years from now will probably look a lot like it does today — regardless of integration levels.

In the two-wheeler market, there are dozens of upstarts bringing their electric products to consumers. And here, we don’t know what will happen. Will ICE players like TVS just smash those upstarts with capital? Will players relying on modular components, focusing on marketing and design, come out on top? Or maybe Oben’s approach will win out, and product differentiation is the right bet?

Another important point is how strong the competition is—especially Ola, which placed a similar bet to Oben. The company is facing regulatory scrutiny, but they sell a hundred times more bikes than Oben, so it’s hard to even compare these companies. The competition overall is very well financed: Ola is a public company, Ather Energy has raised $578 million in total, not to mention all the incumbents like TVS and Bajaj.

Oben is offering a different approach and has a product that doesn’t directly compete with the most popular segment, but it’s still a tough market.

The Bull Case

Outside of the market just being big enough to have room for everyone, I think the main upside comes down to strong product differentiation and brand — enabled by integration. If Oben scales, and if that scale brings down costs while simultaneously improving quality at every level, that’s a winning combination. Tight control over the entire customer experience is hard to pull off, but the potential upside is clear. Becoming the dominant electric motorbike brand is within reach — if the company plays its cards right.

I also want to mention an opportunity to become a supplier to other bike manufacturers. Yes, there are conflicts of interest, but Oben could make it easier for others to enter the market. And given India’s protectionist leanings, building out a domestic supply chain and having the option to pivot into a supplier role later is clearly a strategic advantage.

There’s also the LFP battery bet, but we’ll see how that plays out.

The Potential Power

Inspired by Acquired and Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers, I want to look at which type of strategic power a startup might realistically grow into. These startups don’t have durable advantages yet, but they might. The question is: which power are they most likely to build? The seven are: scale economies, network economies, counter-positioning, switching costs, branding, cornered resource, and process power.

I’m no expert in bikes, but if we look at the car market—especially today—it’s all about the brands. Parts are interchangeable between brands, and everyone has reached massive scale. Yes, there are exceptions like Tesla, but those are, well, exceptions.

And I think Oben can build a brand around reliability and being built in India for India. I think that’s where the opportunity lies. Otherwise, network economies or switching costs—there are none; counter-positioning—too late for that; cornered resource—the company does hold some patents, but I’m not sure there’s really a durable advantage; process power—maybe with all the integration, but again, it’s not like the company invented a new manufacturing process.

So yes, it is about the brand.

The Takeaway

These takeaways are getting more and more out of hand — in that they have absolutely nothing to do with the actual topic. No exception this time.

There are autonomous cars, trucks, buses. But it’s hard to imagine an autonomous motorbike. And I wonder: how would that change cities? Would some places just skip autonomous vehicles entirely? Will there be conflict between bike riders and self-driving cars? Cities are already wildly different — would this make them even more so?

1: It’s likely that the company uses Chinese cells today, since the country holds over 80% of the market.

2: A straight pass ratio tells you what portion of items clear a manufacturing step without needing any touch-ups — essentially the percentage that gets it right the first time without any rework required.

3: There are four more bikes on the page, but they are in a different price range.