It’s Tuesday, and today we are discussing OKO, a Malian insurtech startup. Founded by Simon Schwall, Raphael Haziza, and Shehzad Lokhandwalla, the company recently announced a new funding round led by Catalyst Fund, with additional backing from two existing investors.

The Context

90% of the articles I write cover developing countries — a broad term encompassing everything from the UAE to the DRC.

In this piece, we’ll focus on Mali, a country that has survived not one but two coups in the last five years and is struggling in almost every development aspect.

What probably illustrates this struggle best, and is also relevant to OKO, is the literacy rate, which stands at 35%. To put that into perspective, that’s lower than in Mozambique… over 20 years ago.

As in most countries at this level of development, Mali’s economy is driven by agriculture, with the sector contributing 41.8% of GDP, among the highest in the world. That also means most people work in agriculture, 67.8% to be exact.

I’ve written a lot about African agriculture (MazaoHub, Complete Farmer, Winich Farms). The aspect of farming I haven’t covered yet is insurance. Climate is something farmers can’t control, and without robust tools, improved techniques, and quality inputs, the impact of climate shocks is even more severe.

If a climate shock hits, a farmer can somewhat recover if they have insurance. However, most don’t.

In sub-Saharan Africa, just 3% of farmers have insurance. Considering Mali is among the least developed nations, we can safely assume that insurance penetration there is even lower.

Why is the situation so bad?

Collateral. The most basic reason, and one common across many countries, is that farmers rarely have formal land titles, meaning land often can’t be used as collateral.

Costs for insurance companies. Regardless of the client’s size, insurers must create quotes, collect payments, verify claims, etc. If per-client costs are roughly the same, companies will naturally focus on larger operations.

So while the country experienced 40 major climate shocks in a span of 50 years, most farmers remain unprotected from those very shocks.

And while insurance allows farmers to recover losses, in Mali’s case it does more than that by enabling investment in their future. A survey of OKO’s customers found that 25% of those who bought insurance planted larger areas, 10% bought more fertilizer, and 8% bought better seed.

On a broader scale, one study found that increasing farmers’ access to insurance increases investment by 20–30%.

Not to be overly dramatic, but in many ways, insurance is the difference between farms going bust after a climate calamity and being able to invest in the future.

The Product

OKO provides affordable weather-index insurance to farmers across Mali and other African countries. To calculate the risk of adverse climate events, the company uses satellite imagery, weather forecasts, and 25 years of historical weather data. The same data is used to issue payouts when risks materialize. Its granularity is around four square kilometers, meaning precision is at the village level rather than the individual farm level.

The insurance covers both drought and flood risks. Payouts are determined by comparing rainfall in a specific area during the season to historical averages.

While the core product is no doubt important, that, however, is not the interesting part. That would how the product is delivered, how the local context shapes the customer journey.

1. Discovery. I’ve mentioned the developmental problems that Mali experiences. There is, however, a bright spot. There are 112 mobile subscriptions for every 100 people, and 54.8% have an account at a financial institution (most of that is mobile money). Both are on par with Mexico. OKO capitalizes on that, with mobile and radio being the core channels for prospective customers to hear about OKO.

2. Quote request. When farmers ask to register, a call center agent gets back to them to clarify location, crop timing, and the weather insurance quote. While the SMS menu is accessible to all, farmers may lack battery, network coverage, or literacy to use it. To address this, OKO lets them schedule a call-back at a convenient time. Customers with mobile internet may use WhatsApp, but many prefer voice notes instead of typing. To work with those farmers, the company created a voice-note chatbot, so those who cannot read or write can still communicate with OKO through digital channels.

3. Payment. Using the same rails, i.e. SMS and mobile money, the company first facilitates quote distribution and then payments for the plan. Unfortunately, some farmers cannot afford to pay for the plan. OKO found a way to work with those farmers too. About 1.3 million Mali-born immigrants live abroad, and many send money home, with remittances accounting for 4.1% of the country’s GDP. Through partnerships with the NGO ADA and payments provider Flutterwave, the company made it possible for emigrants to buy insurance for their farmer relatives.

The end-product value is this combination of solving a real problem, delivering the product by adapting to the local reality (and trying to change it), and helping farmers invest in the future.

The Business Model

To make the business viable in a market where customers have limited financial capacity and tech solutions are hard to scale, OKO had to build a different model from traditional insurers in the region.

First, it tries to limit costs associated with conventional crop insurance, things like sending agents to inspect farms or assess crop damage.

Second, it uses low-tech distribution channels that are still high-tech enough to reach potentially millions of farmers at low marginal cost, but simple enough to allow two-way communication. Agents are still used to acquire farmers who are hard to reach or prefer in-person interaction. For each farmer they onboard, the company pays a commission.

OKO, however, doesn’t rely solely on its own resources to grow. It partners with microfinance institutions (MFIs) and mobile network operators, offering clear value to both:

Because farmers are financially protected against worst-case scenarios, MFIs can reduce default rates and late payments.

Network operators generate additional income by taking a commission on payments.

Monetization

The company sells policies with an average premium of about $20, covering 1.5–2 hectares of land. Policy purchases and payouts are both handled through mobile money accounts. Farmers who don’t have sufficient funds can pay in installments. For 97% of farmers, this is their first-ever insurance product.

Results

The Bear Case

The biggest roadblock on OKO’s path is acquisition.

The company has been transparent about the challenges it faces in reaching farmers. In one interview, though five years old now, Simon mentioned that their customer acquisition cost (CAC) was $9, while the average premium cost $10. That’s why OKO has been shifting toward less expensive customer acquisition channels.

However, this shift isn’t simple. A GSMA survey shows that 54% of farmers still need assistance making payments, including through mobile money agents. Moreover, 73% still prefer to register for insurance through an agent, even when they’re repeat customers.

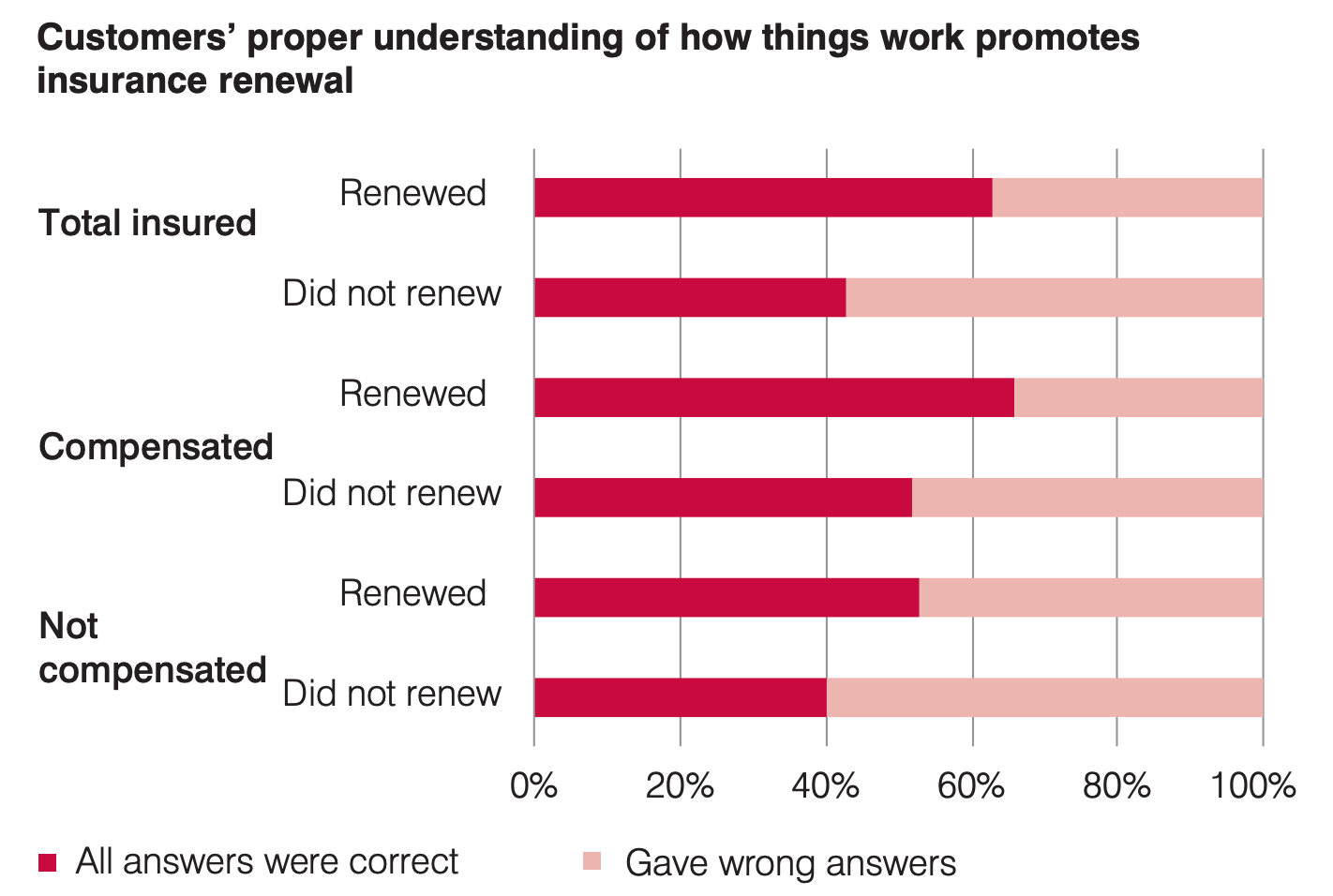

Beyond reaching customers, there’s also the challenge of explaining the product’s value. If people don’t understand what they’re buying, they’re less likely to renew. Even among those who do renew, 40% still don’t fully understand how their policy works.

That brings up a tough question — who should OKO target first: those most likely to convert or those least likely? If it focuses on the former, scaling will eventually mean working with farmers who have less awareness of insurance and are more likely to churn. Add to that the difficulty of reaching them in the first place, and the acquisition challenge becomes even greater.

The Bull Case

The potential market is in the many millions of farmers. As climate shocks become more frequent, both first-time purchases and renewals should rise. Combine the two, and if OKO manages to scale through digital channels layered on top of partnerships, rather than relying on agents, it could grow faster and with lower CACs.

Additionally, while for now OKO has focused on geographic expansion, but there’s also room for product expansion. For instance, it could introduce insurance tailored to specific weather events.

The Takeaway

I never thought of insurance as an enabler. I always saw it as a risk mitigation tool — something you buy in case things go wrong, like travel insurance for lost baggage.

But in the case of OKO, and farmers across Africa, insurance actively changes behavior. It makes farmers willing to expand their land or invest in proper fertilization.

When you see data confirming that connection, it feels obvious. But it’s not something you think about until you do.